One Planet News: A revolutionary way of studying bird brains

Bird brained? Study shows this is just not true

Scientists are trying to learn more about birds thinking patterns when they fly by looking inside birds’ heads.

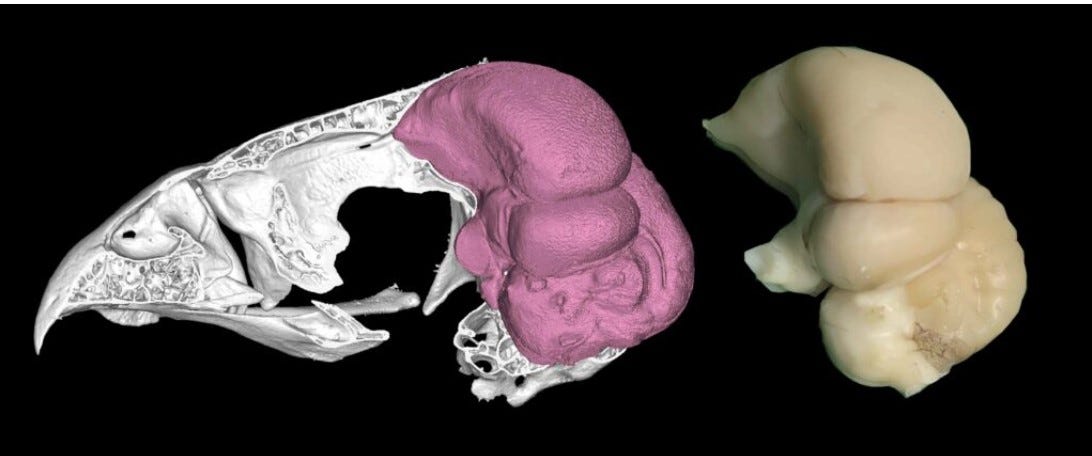

Evolutionary biologists and neuroscience researchers have teamed up to recreate the brain structure of both living and extinct birds. Researchers are using digital ‘endocasts’ from the area inside a bird skeleton’s empty cranial space.

The study, published in Biology Letters, was led by the Bones and Diversity Lab at Flinders and the Iwaniuk Lab at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta. Scientists found that the skulls of long-dead birds in museums could provide detailed information on a species’ brain to consider smartness and nimbleness.

Read more: UK adults lack connection to nature

Lead author from Flinders University, PhD Aubrey Keirnan said: "This showed that the two correspond so closely that there is no need for the actual brain to estimate a bird's brain proportions.

"While 'bird brain' is often used as an insult, the brains of birds are so large that they are practically a braincase with a beak. We decided to test if this also means that the brain's imprint on the skull reflects the proportions of two crucial parts of the actual brain."

The discovery was made possible by comparing historical microscopic sections of the brain with digital imprints of the bird's inside braincase.

This is the largest study of its kind covering 136 species.

The team were joined by researchers at the Department of Neuroscience at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada. Skulls from 136 bird species were scanned for which they also had microscopic brain sections or literature data.

This allowed them to determine whether the volume of two crucial brain parts, the forebrain and the cerebellum corresponds with the surface areas of the endocasts. Researchers were surprised by the tight match between the real and digital brain.

Read more: Deadly ambush predators

Senior co-author and Associate Professor Vera Weisbecker from Flinders University's College of Science and Engineering, said: "We used computed microtomography to scan the bird skulls. This allows us to digitally fill the brain cavity to get the brain's imprint, also called an 'endocast.

"The correlations are nearly 1:1, which we did not expect. But this is excellent news because it allows us to gather insight into the neuroanatomy of elusive, rare and even extinct species without ever seeing their brains.

"The great thing about digital endocasts is that they are non-destructive. In the old days, people needed to pour liquid latex into a brain case, wait for it to set, and then break the skull to get the endocast.

She added: "Using non-destructive scanning not only allows us to create endocasts from the rarest of birds, it also produces digital files of the skulls and endocasts that can be shared with scientists and the public."

Professor Andrew Iwaniuk from the University of Lethbridge has an extensive background in bird brain research.

He said: "While most of the telencephalon (outer part of the forebrain) is visible from the outer surface, a substantial portion of the cerebellum is obscured by this region. Additionally, the avian cerebellum has 'folds' which are often obstructed by a large blood vessel called the occipital sinus.

"Given that the degree of obscurity can vary between species, I did not expect a strong correlation between endocast surface area and brain volume across all species."

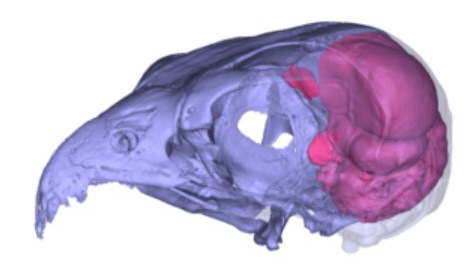

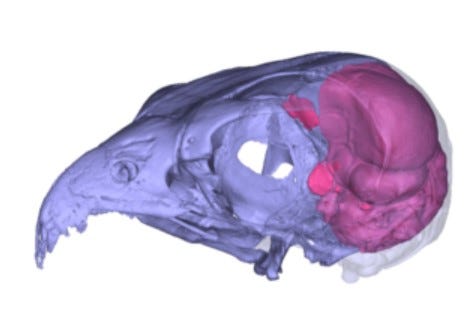

Photo credits. Image 1: Digitally reconstructed skull and endocast of an Australian hobby falcon (Falco longipennis).

Image 2: Shows a digitally reconstructed skull and endocast of a Collared Sparrowhawk (Accipiter cirrocephalus; left) and the brain of a Cooper’s hawk (Astur cooperii; right) showing the similarities between endocasts and brains of two related species.

Graphic by Aubrey Keirnan and Andrew Iwaniuk.

One Planet News: Science study into migratory songbirds gives fascinating insight

Wild Insights Supplement